We at Team Spacemesh dedicate our work to the youth of the world today, who’ve inherited a world that is far worse off than their parents had to deal with. A world of climate change, inflation, and polarization. A world which has let them down. We know you look outside to the world with fear and frustration, wondering how previous generations messed up so badly to bring us to this low and fragile point in “modern” civilization.

We are here to tell you: you have a role to play in what comes next, there are better futures ahead, more inline with our group human-values if you choose to build them!

“I realize then that the disappearance of a culture does not signify the disappearance of human value, but simply of certain means of expressing this value, yet the fact remains that I have no sympathy for the current of European civilization and do not understand its goals, if it has any. So I am really writing for friends who are scattered throughout the corners of the globe.“

- Culture and Value, Ludwig Wittgenstein 1970

What Is Up?

Thank you for reading this and for caring about the future of society and how we can do better. As anyone can see, there’s something going on in the world that’s in need of explanation. The majority of us are good folks, yet somehow our reality seems to be getting nastier and more malevolent by the second. We’ve grown to accept a reality where human values innate to us all, and existing incentives structures — what it takes to “make it”, these days — are at odds with each other.

Money is the most significant way we coordinate human action right now, but it’s also what’s dividing us: taking over our landscape and public places, forcing us to compete fiercely even if we find it distasteful. This is the reality that, increasingly, many young people are “opting out” of, choosing instead to live a life of near solitude, basically choosing not to engage with society, reducing our social life to the nuclear family—and sometimes not even that. Others, without the means to “opt out”, try to survive within the cheap old game, where any aim to play with the rules rather than by the rules is luxury only the privileged can afford.

But this messed-up status quo is not inevitable. It’s not some act of God or “human nature”. Rather, there is a systemic reason in play: According to our modern (neoclassical) economics, the very best most efficient way to organize human activity is essentially stoking self interest in so-called “free markets”. The theory claims that, in a perfectly competitive market, individuals can be guided by self-interest to benefit the whole of society, since the autonomous actions of selfish individuals will lead to an outcome that is ‘Pareto optimum’, based on the notion of ‘invisible hand’ (Adam Smith 1776 ) foundational to neoclassical economics.

This idea of treating economy like astronomy, i.e. the ‘physics of human-behavior’ is based in a fundamental misunderstanding of humanity. It treats human beings as ‘homo economicus’, driven at all times by seeking out the most ‘rational’ course.

But this is not how social organisms function—not in any recorded instance. Because what is ‘rational’ in a social context differs fundamentally from what is ‘rational’ in an atomized one. All social beings face a fundamental dilemma: actions that are best for the group as a whole do not always maximize relative fitness of individuals within the group. To resolve this tension, social organisms find ways to suppress the self interest of individual group members.

In defiance of the armchair theorizing of many 19th-century thinkers, small-scale societies are not anarchic free-for-alls. They are, in fact, very tightly regulated by what anthropologists call the “tyranny of cousins”. In a small-scale society, everyone knows everyone, and everyone keeps tabs on everyone. Norm violators are harshly punished by shunning, exile, or—in very extreme cases–execution.

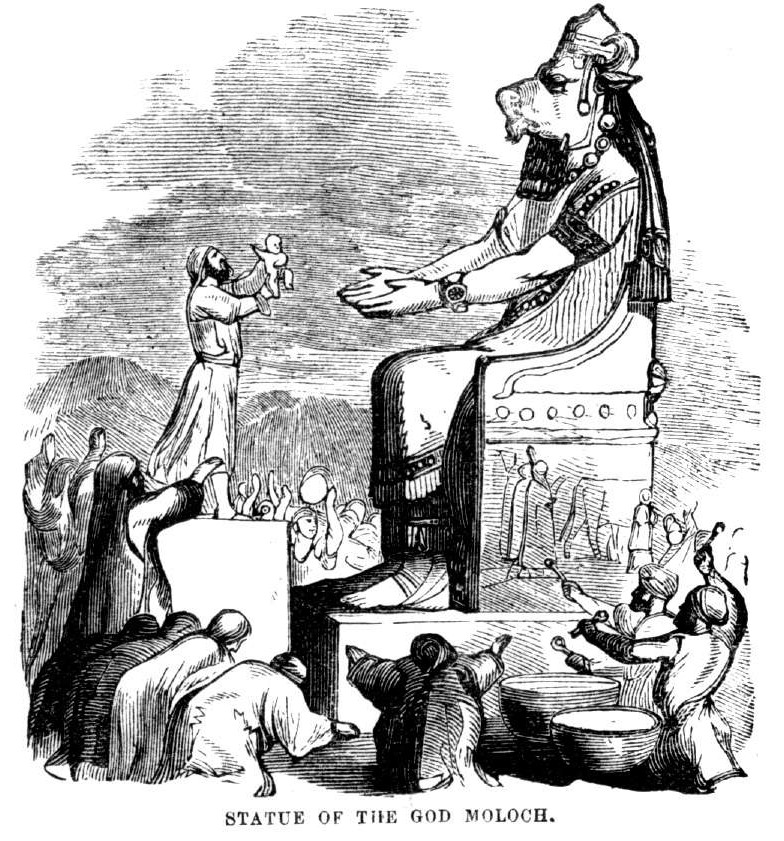

Moloch: the demon of coordination failure

The anonymous society, by contrast, is a very recent development in human history, where all of these natural ‘immune responses’ fall by the wayside. This is a function of millions of people living in huge urban centers, often with only weak ties to their nuclear families—let alone their extended families. This break from the “tyranny of cousins” is in many ways a positive development, as the tyranny of one’s kin is no less tyrannical than that of the centralized state. But this has left us in a far truer state of anarchy than our ancestors ever experienced. One that allows bad actors to flourish as never before.

In an anonymous society, there is no ‘invisible hand’ to regulate agents pursuing their own self-interest into agents who benefit society. No more than there is an ‘invisible hand’ to regulate the organisms that exist within the fragile equilibrium of our bodies. Like our bodies, our economies and societies are complex and adaptive systems. And like our bodies, a lack of an ‘immune system’ often leads to disease. Therefore, instead of ‘laissez faire’, we need something more to regulate our behavior.

But what does ‘something’ look like, if not a ‘tyranny’ of some sort? (Tyranny, it should go without saying, is something we should avoid at all costs.)

One of the biggest dangers to social groups is the problem of free riders; individuals who behave parasitically by benefiting from the altruism and protection of the group, without doing their fair share in return. In small-scale societies, finding and stopping free riders is a fairly simple matter. But in large-scale, anonymous societies, they often pass under the radar.

We’ve now reached a point that’s even more dire than this, however: in our society, free riders are flying on the radar. They are getting away with selfish behavior at the expense of the whole, and we are knowingly letting them do so.

Several aspects of our society enable this to happen. For one thing, values are needed to govern, bind and guide the extension of human systems, including the economy, our technology and our culture. But how can we know which values should govern us?

Currently, we are living in a world dominated by the values of the so-called Enlightenment. An obsession with progress for its own sake, coupled with the belief that humanity is perfectable—that all we need to do to reach an everlasting utopia is to unlock the right cheat codes to make ‘homo economicus’ function exactly as is good for a vague, abstract kind of ‘progress’ that must continue in perpetuity.

In fact, we’re so conditioned to think of progress as a good unto itself that there may be some confusion as to why I’m citing an obsession with it as one of the foibles of our current world.

Obviously, people becoming better off—materially, emotionally—is a worthy pursuit. But how often has the conscious pursuit of ‘progress’ for its own sake actually resulted in good outcomes? On the contrary, those acting in the name of progress have done some of the most monstrously evil things that humanity has ever witnessed.

This is because the notion of ‘progress;’ exists in a world of formal, rather than material logic. What this means is that it is purely conceptual, wholly divorced from anything bounded by material reality.

This is why believers in ‘moral progress’ can look back on the past with a sanctimonious sense of moral superiority. To them, the material constraints of the past, which shaped its morality, are simply irrelevant. Their sense of morality is essentially supernatural—though its proponents will insist it is the most natural thing in the world.

‘Progress’ is not what we should be looking for, but adaptation. Adaptation is not directional, but functional. Adaptation, by definition, occurs in response to the material world, and is always in friction with it.

But adaptation can also lead to outcomes that are undesirable from the perspective of maximum human flourishing. For example, humans have many adaptations that can lead to cruelty and selfishness.

Is there a way for us to adapt mindfully?

Darwin: the next "Adam Smith"

Earlier in this piece, we discussed how groups function as a kind of superorganism. And in fact, we can think of human society as a superorganism composed of other, smaller superorganisms, where the logic of within-group and between-group selection is applicable in each case.

We’re already familiar with within-group selection, which is how our basic understanding of evolution already functions: those individuals with the greatest ‘fitness’ are the most likely to survive and produce offspring. Between-group selection functions in a similar fashion: the groups that are the fittest are the most likely to survive, reproduce themselves, and grow. But within-group and between-group selection are often at odds, and this becomes more understandable once we think of groups as superorganisms.

Consider the mystery of suicide: why would natural selection introduce behaviors that lead to the death of an organism, making it unable to reproduce? This is clearly inexplicable if the only forces acting on our evolution were within-group selection, as all the explanations involve some kind of group-mediated selection.

One hypothesis would be kin selection—where the death of the individual provides a survival advantage to their most closely-related kin. But this seems highly unlikely to be the case, since individuals without any known relatives are arguably even more likely to commit suicide.

In fact, suicide most closely resembles a well-documented biological phenomenon: programmed cell death. That is, the process by which cells destroy themselves, because they have outlived their usefulness to the larger superorganism to which they belong.

Now, suicide is obviously an awful thing, and we should do everything in our power to rid our world of it entirely. Something being natural and explicable does not make it good. But we cannot deny that the risk factors for suicide, such as social isolation, or shame, give feedback to the individual that they are no longer a “useful part of the superorganism”.

This tragic outcome is very compelling evidence for the existence of between-group selection, and handily demonstrates the tension that exists between within-group and between-group selection.

What’s good for you can be bad for your nuclear family. What’s good for your nuclear family can be bad for your extended family. What’s good for your extended family can be bad for your city. What’s good for your city can be bad for your nation. What’s good for your nation can be bad for the world. Each of these tiers of social organization represent their own superorganism, subject to their own unique selection pressures.

Keeping this context in mind, we can see how an observer’s intuitive judgment is often misguided: adaptation at any level of a multi-tier hierarchy of superorganisms in undergoing a process of selection — and it can be undermined by the simultaneous processes of selection at lower levels. This may seem, at first, to be too complex and abstract to be of any consequence. But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Because ignorance of this context leads to a fundamentally misguided vision of the world, where we cannot possibly grasp what is actually best for society. After all, which “society” (that is, which superorganism) are we talking about?

But the most pressing question of all is, of course: how do we bring the constituent superorganism into equilibrium with the super-superorganism that we call “humanity”? Now that we know that it exists, is it possible to harness the power of group selection to bring about genuine, sustainable progress?

Conscious Evolution

Evolution is a natural process, and is presently also an unconscious one. But it doesn’t have to remain unconscious.

If this is making some alarm bells go off in your head because it reminds you of 20th-century pseudoscience like eugenics or “social darwinism”—allow me to put your mind at ease. I am not talking about genetics at all, or the ludicrous idea that “races” are in some kind of battle royale for supremacy. In fact, it’s the exact opposite: these ideas exist firmly in the ‘progress’ camp, with eugenics being happily embraced by the ‘progressives’ of the early 20th century.

But conscious evolution is not about ‘progress’. It is about mindful adaptation to maximize human flourishing through cooperation.

As it stands, we are without a unifying worldview that can point to our place and purpose in the universe while also withstanding rational scrutiny. This puts us in a precarious position, where millions of ideas are being sold by millions of preachers, intellectuals, pundits and “influencers” as the ultimate meaning in life — religion, mental and physical practice, sensory stimulation of all sorts.

So here’s OUR solution to everything!

Just kidding. ;)

These kinds of “one-size-fits-all”, “ultimate” solutions are a big part of the problem. Far too many times, it’s well-intended, sometimes even genuinely altruistic leaders responsible for some of the most harmful decisions as discovered in retrospect. They think they have it all figured out, and that’s just about the most dangerous thing that anybody in power can believe. The future is unpredictable, and the path forward is always “yet to be forged”; landmines and “known failure modes” cannot possibly be reliably avoided, and ANY all-encompassing utopian solution is doomed to failure.

In light of all this, one might wonder why we’re so certain that mindful adaptation is even achievable. Perhaps this status quo is the best we can do between untrustworthy, selfish-by-nature humans. What could possibly be a practical way to suppress “lower-level” selection pressures and allow for “higher-level” selections to robustly prevail?

Well, for starters, we need a change in perspective. We need to zoom out and change the “unit of selection” from individual selfish organisms to the superorganisms composed of them.

Take the humble bee: it is a unit of functional organization in some respects, but in other respects it is more like a cell participating in the functional organization of the hive. Its cell-like status is due to the fact that many traits in honeybees evolved for the sole purpose of ensuring the survival of the hive, with the chief source of competition being other hives rather than other individual bees. For as long as the hive becomes the unit of selection, it becomes the anchor of our functional analysis.

But are humans similar enough to honeybees for this comparison to have any merit?

In some ways, yes. We are admittedly not usocial like bees, ants, termites, or naked mole-rat (the only truly usocial mammal). We do not entirely sublimate our individual benefit for the benefit of society. But we are hyper-social in a way that can only be compared in scale to usocial insects. Ants, in particular, who are the only other known organism besides human beings to engage in behaviors like traffic lanes and agriculture. And though we are not quite as willing to sacrifice ourselves for the good of the hive, or the “queen”, we are also not without those inclinations. The millions of people who have marched off into battle, often with full knowledge of what it will likely cost them, is a testament to this. As is the example of suicide which we explored earlier.

We also have several “superpowers” that are entirely unique to our species, and all of them exist in the realm of the social. Language, narrative, and abstract thinking are all employed to make us function better within a group. A language with only one speaker is dead; a story without any listeners is untold.

So, for humans, we can say with a great deal of confidence the “unit of selection” is chiefly that of the group. And it’s only once we embrace this shift in perspective that we can begin to implement conscious evolution.

Welcome to the biological future

Welcome to the biological futureGoing deep into this question is the polymath David Sloan Wilson, who explained in 2007 that “Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary”. This tidily sums up the tension that exists between within-group and between-group selection, and how an equilibrium is reached between the two. When selfishness becomes too dominant within a group, cooperation breaks down, and more coordinated, cooperative groups will beat it every time. But organisms that are purely selfless will die out before they ever have the chance to reproduce, because more cutthroat individuals will prey upon them.

A little bit of selfishness is healthy. A lot of selfishness spells doom for the long-term prospects of a superorganism. How do we activate the altruistic, cooperative psychology that allows us all to flourish the most, without also activating some of the more unsavory aspects of between-group selection—such as violent group conflicts and scrambles for resources?

How do we avoid the ‘tragedy of the commons’?

The Avoidable Tragedy

Elinor Ostrom, awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic (2009)

Enter Elinor Ostrom, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for her “analysis of economic governance, especially the commons”, which she shared with Oliver E. Williamson. Through her research, she identified 8 principles for governing collaborative effort in the optimal way. Namely:

1. Commons need to have clearly defined boundaries.

2. Rules should fit local circumstances.

3. Participatory decision-making is vital.

4. Commons must be monitored.

5. Sanctions for those who abuse the commons should be graduated.

6. Conflict resolution should be easily accessible.

7. Commons need the right to organize.

8. Commons work best when nested within larger networks.

Or, put another way:

- Our collaborative efforts can’t be a free-for-all. There need to be clear rules around who gets what, when, and where.

- No universal rules exist, because no universal material conditions exist. These groups need to exist on a local level and tailor their rules around what’s logical on the ground.

- People are more likely to follow rules that they helped to create.

- There needs to be a way to make sure that people are following the rules. If there’s no way to make sure, the rules may as well not exist.

- Harsh punishments for first-time offenders only cause resentment. People need to be given chances to do the right thing by starting out with consequences like warnings, fines, or a lowered reputation.

- There should be cheap and easy ways for people with disputes to find mediation.

- Rules that aren’t legitimate in the eyes of the “powers that be” cannot be enforced, and that makes them pointless.

- Local management is optimal, but sometimes it isn’t enough. The ability to cooperate with groups in other locales is extremely important.

These may seem like simple common sense, and yet our system consistently falls short of applying them. They may also seem, on the surface, to be entirely unrelated to conscious evolution. But they are actually essential.

Unconscious group selection will happen regardless of anything we do. The “tragedy of the commons” is very real, and is a prime example of this process in action; just think of how many of our problems come down to a failure to apply the first principle. We see this runaway group selection in the realm of geopolitics, religion, and of course economics.

What these guidelines do is provide a way to consciously direct our evolved social psychology for the betterment of our communities.

In other words, they are the blueprint for conscious evolution. The way we can facilitate the lower rungs on the superorganism hierarchy serve the interests of the higher ones. How we can come together in a decentralized fashion to consciously evolve ourselves in a fashion that maximizes our flourishing—that is dynamic and adaptive for the complex system that is the human collective.

And where does Crypto fit into all of this? So much ink has been spilled over the ethical implications of Bitcoin and the Cryptocurrency industry, often conflating the morality of some individual bad actors with the virtues of cryptocurrency as a technology. It seems to be a journalistic hobby, in fact, to use every single wave of crypto juvenile delinquency to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

But as Olaf from Polychain has said: “decentralization and all these systems, is not an ideology thing, but it’s really just an architecture”.

An architecture that can serve as a foundation stone for a humanity that is consciously evolving itself.

Perhaps it is the missing ingredient to break us out of this feedback loop of technology leading us to race faster and faster with our eyes increasingly closed. To free us from our post-Enlightenment obsession with finding data-driven static solutions, so we can mindfully adapt ourselves, our culture and our economy, as an inter-connected, complex living system.

A new and improved system to collectively get our mutual needs met, without devastating the planet or behaving sociopathically to each other. Can cryptocurrencies’ architecture be a springboard for a revolution in human values? Giving humanity an immutable ledger of the past which cannot be altered by those who want ‘progress’ at any cost; giving groups the ability to, through technology like smart contracts, enact Ostrom’s eight principles in a far more streamlined and efficient way.

Perhaps, on its own, it is not sufficient. But it is necessary. The vital building black of a new kind of future.

Crypto-enabled, self-organizing, well-integrated: a superorganism composed of superorganisms, nested and meshed together, vastly more resilient and prosperous than the sum of their individuals. Crisscrossing and switching between different modes of organization, capturing meaning together.

Evolving consciously together.

Join our newsletter to stay up to date on features and releases